Uncovering the mystery of negative dysphotopsia

Uncovering the mystery of negative dysphotopsia

What we know, what we don't know, and what we can do about it

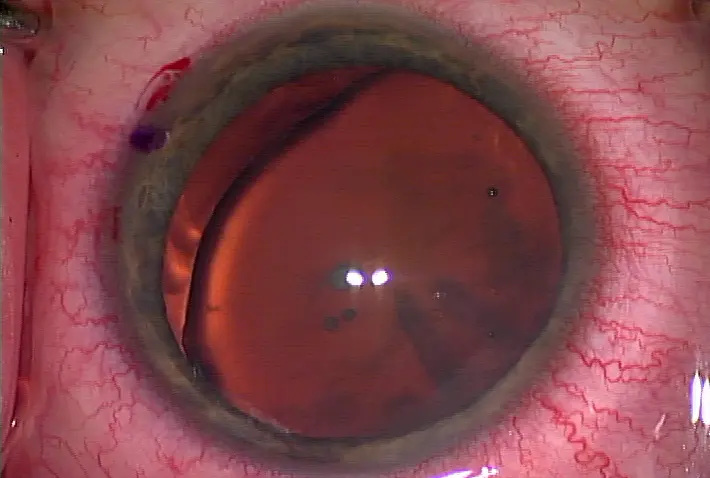

It's always concerning to hear surgeons say, "I don't know; it's a mystery," when speaking about a medical phenomenon. Physicians live and breathe facts and data on who develops a condition and why and what can be done to treat it. But with negative dysphotopsia, the answers to many of those questions are puzzling. "We don't really know what it is, and we don't understand it very well," said James Davison, M.D., cataract and refractive specialist, Wolfe Eye Clinic, which has locations throughout Iowa. "It only seems to happen in people who have perfect surgery. Everything else looks absolutely perfect and then they have this difficulty." This difficulty, or negative dysphotopsia (ND), comes in the form of a black line, a parenthesis out of the patient's peripheral vision often described as a dark shadow. "The typical thing they will say is to envision a horse with blinders," said Samuel Masket, M.D., clinical professor of ophthalmology, Jules Stein Eye Institute, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles. "That's what it looks like to them. They can't see to the side."

What causes ND?

The maddening thing about ND is doctors haven't been able to nail down why this phenomenon happens or to whom it will happen. There are plenty of theories about what causes ND and what to do about it, but not much has been proven clinically. Different physicians have different stories. For example, Kevin Miller, M.D., professor of clinical ophthalmology, Jules Stein Eye Institute, Los Angeles, believes ND is directly related to the square-edge shape of the implanted IOL.

"It has something to do with the square edge," said Dr. Miller. "With rounded-edge lenses, no one ever complained about this kind of thing."

Dr. Miller believes ND occurs because light coming into the pupil from the temporal field of vision causes the problem. When light hits the square edge of the IOL on the nasal side of the optic, the edge acts like a plano mirror, reflecting light off the edge. This light then bounces back to the temporal side of the retina, causing one of several positive dysphotopsias, and doesn't get through the edge to illuminate a patch of nasal retina, thus casting an arc-shaped shadow over the area. He explained this theory in the August 2005 issue of the Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery (31:1488-1489). "The interesting thing is we started seeing this with the square-edge silicone lenses, although it wasn't as bad with the silicone as it was with acrylic," he said. "So it has something to do with the square edge and a little bit to do with the material." Likewise, Dr. Davison believes ND is lens-shape related, although he's unable to pinpoint precisely why. "I think it has something to do with the shape of the lens we put in the eye versus the shape of the lens we take out," he said. "I think we probably saw things like this before the square edge, but the square edges seem to make for more frequent complaints. There might be some internal reflections; there might be some sort of edge effect. Some papers show that you can still have ND even if you put in a round-edge IOL."

Dr. Masket, on the other hand, believes ND is generated from the overlap of the anterior capsulorhexis onto the anterior surface of the IOL. He wrote about this and the surgical techniques to quell it in the July issue of JCRS (37:1199-1207). "The most important thing about ND is that it only occurs with the lens in the bag," Dr. Masket explained. "It can occur with any lens in the bag. I think it's still controversial whether some lenses are more prone than others. People often point to the AcrySof lens [Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas] as being significantly causal, but they overlook the fact that more than half the lenses implanted in the world are the AcrySof lens."

Patient patterns

Just as no one fully understands why ND occurs, doctors are unable to anticipate who will become symptomatic. Drs. Masket and Miller have picked up on a couple of trends, but evidence is antidotal for now. "When we look at the demographics of patients with this condition, there is kind of a blip on the screen where there will be more women in their 50s than any other gender or age group," Dr. Masket said. "I won't say that's hard data, but that's pretty much what we see. It's odd. It hasn't been carefully analyzed." Dr. Miller notices a comparable personality thread throughout his ND patients. "I think the pattern is the more observant the patient, the more technical she is, the more engineer-like, the more she is likely to notice it," he said. In terms of who won't become symptomatic, Dr. Davison hasn't seen ND in patients who are extremely nearsighted. Dr. Masket has never had an ND complaint from a child, although he hasn't done a large number of pediatric cataract cases. He also stressed ND has never been reported in a sulcus-placed lens or with an anterior chamber lens. "The only thing I've proven clinically is if you take the lens out of the bag, the problem goes away," Dr. Masket said.

Solutions

Luckily, most cases of ND fade with time and rarely need surgical intervention. If ND is going to dissipate on its own, it will be in the first 6 months. But it doesn't always. A handful of patients will remain symptomatic a full year later. Why ND diminishes in some patients and continues to plague others is a mystery. Likewise, no one knows for sure why ND clears up in the first place. Some surgeons believe the patient adapts to the phenomenon over time and stops noticing it as much. Dr. Miller, however, disagrees with that theory. "They don't just get used to it," he said. "It would be like trying to get used to having a ball and chain attached to your foot. You might learn to live with it, but you wouldn't ever get used to it or act like it's not there. I don't think there are patients getting used to it or neuroadapting to it. I think it actually goes away." Dr. Miller believes ND disappears because lens epithelial cells begin to pack into the space between the front and back capsule at the edge of the lens, reducing the difference in refractive index between the inside lens and just outside the lens. "They make the edge of the lens leaky to light," he said. "The light that leaks out illuminates the nasal retina and the shadow goes away." Because ND could simply go away, all surgeons interviewed recommended waiting at minimum of 3 months, but ideally 6 months to a year, before trying anything surgically. During that time period, having the patient wear thick-framed glasses might alleviate the symptoms. "We always try to get patients out of glasses, but this is one case where glasses do help," said Dr. Davison. "Glasses can obscure the image so it makes it less distracting. It puts the shadow in the same category as a frame, and [the patient] doesn't notice it anymore."

"Anything that will block a source of light on the temporal side, like a pair of spectacles, will reduce the symptoms," said Dr. Masket. "Unfortunately, that's not a satisfactory answer for many patients. If you can get thick-framed glasses, it's a good suggestion. It's worthy of a try."

If a patient bucks at wearing glasses, it's time to consider surgery. Dr. Miller's preference is to do a full lens swap, taking out the offending IOL and replacing it with a rounded-edge or plate haptic lens in either the bag or the sulcus.

"I'll put in a plate haptic lens like a STAAR Surgical collamer lens (Monrovia, Calif.) and will orientate the plate haptic in the 3 to 9 o'clock orientation," Dr. Miller said. "The optic is continuous with the haptic, so there's no lens edge to cause that problem anymore." Inserting a "piggyback" IOL, which was first reported by Paul H. Ernest, M.D., associate clinical professor, Kresge Eye Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, is another surgical technique that's proven successful. Dr. Masket explained this technique in detail in the September 2011 issue of EyeWorld (page 16). A video of Dr. Masket's technique is available at www.eyeworld.org/replay.php.

"It's a simple surgery that brings with it a high degree of both technical success and the alleviation of symptoms," said Dr. Masket. "I have heard reports where it hasn't helped 100% or even at all. Nothing is 100%, although in our research, we had either complete or significant reversal of symptoms.

"The problem is you have a condition on which people don't have good facts, and they have a lot of emotions so you get a lot of opinions," Dr. Masket said. With so little clinical understanding of ND, it's easy to see why the phenomenon both frustrates and captivates physicians. Even with a physical intervention, there will be the occasional patient who surgery won't help. In those cases, said Dr. Davison, it's up to the doctor to be a physician instead of a surgeon. "A surgeon repairs things, but a physician sits and listens to the patient and councils him through problems," said Dr. Davison. "You can explain all the wonderful advances we have, and there are miraculous techniques and materials that we work with, but they are not like the good Lord's original equipment. There are limits to what we can do."

Editors' note: The doctors interviewed have no financial interests related to this article.

Contact information

Davison: jdavison@wolfeclinic.com; via RN Carol Loney, cloney@wolfeclinic.com

Masket: sammasket@aol.com; via assistant Ann McLean, avcweb@aol.com

Miller: kmiller@ucla.edu

by Faith A. Hayden EyeWorld Staff Writer

It's always concerning to hear surgeons say, "I don't know; it's a mystery," when speaking about a medical phenomenon. Physicians live and breathe facts and data on who develops a condition and why and what can be done to treat it. But with negative dysphotopsia, the answers to many of those questions are puzzling. "We don't really know what it is, and we don't understand it very well," said James Davison, M.D., cataract and refractive specialist, Wolfe Eye Clinic, which has locations throughout Iowa. "It only seems to happen in people who have perfect surgery. Everything else looks absolutely perfect and then they have this difficulty." This difficulty, or negative dysphotopsia (ND), comes in the form of a black line, a parenthesis out of the patient's peripheral vision often described as a dark shadow. "The typical thing they will say is to envision a horse with blinders," said Samuel Masket, M.D., clinical professor of ophthalmology, Jules Stein Eye Institute, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles. "That's what it looks like to them. They can't see to the side."

What causes ND?

The maddening thing about ND is doctors haven't been able to nail down why this phenomenon happens or to whom it will happen. There are plenty of theories about what causes ND and what to do about it, but not much has been proven clinically. Different physicians have different stories. For example, Kevin Miller, M.D., professor of clinical ophthalmology, Jules Stein Eye Institute, Los Angeles, believes ND is directly related to the square-edge shape of the implanted IOL.

"It has something to do with the square edge," said Dr. Miller. "With rounded-edge lenses, no one ever complained about this kind of thing."

Dr. Miller believes ND occurs because light coming into the pupil from the temporal field of vision causes the problem. When light hits the square edge of the IOL on the nasal side of the optic, the edge acts like a plano mirror, reflecting light off the edge. This light then bounces back to the temporal side of the retina, causing one of several positive dysphotopsias, and doesn't get through the edge to illuminate a patch of nasal retina, thus casting an arc-shaped shadow over the area. He explained this theory in the August 2005 issue of the Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery (31:1488-1489). "The interesting thing is we started seeing this with the square-edge silicone lenses, although it wasn't as bad with the silicone as it was with acrylic," he said. "So it has something to do with the square edge and a little bit to do with the material." Likewise, Dr. Davison believes ND is lens-shape related, although he's unable to pinpoint precisely why. "I think it has something to do with the shape of the lens we put in the eye versus the shape of the lens we take out," he said. "I think we probably saw things like this before the square edge, but the square edges seem to make for more frequent complaints. There might be some internal reflections; there might be some sort of edge effect. Some papers show that you can still have ND even if you put in a round-edge IOL."

Dr. Masket, on the other hand, believes ND is generated from the overlap of the anterior capsulorhexis onto the anterior surface of the IOL. He wrote about this and the surgical techniques to quell it in the July issue of JCRS (37:1199-1207). "The most important thing about ND is that it only occurs with the lens in the bag," Dr. Masket explained. "It can occur with any lens in the bag. I think it's still controversial whether some lenses are more prone than others. People often point to the AcrySof lens [Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas] as being significantly causal, but they overlook the fact that more than half the lenses implanted in the world are the AcrySof lens."

Patient patterns

Just as no one fully understands why ND occurs, doctors are unable to anticipate who will become symptomatic. Drs. Masket and Miller have picked up on a couple of trends, but evidence is antidotal for now. "When we look at the demographics of patients with this condition, there is kind of a blip on the screen where there will be more women in their 50s than any other gender or age group," Dr. Masket said. "I won't say that's hard data, but that's pretty much what we see. It's odd. It hasn't been carefully analyzed." Dr. Miller notices a comparable personality thread throughout his ND patients. "I think the pattern is the more observant the patient, the more technical she is, the more engineer-like, the more she is likely to notice it," he said. In terms of who won't become symptomatic, Dr. Davison hasn't seen ND in patients who are extremely nearsighted. Dr. Masket has never had an ND complaint from a child, although he hasn't done a large number of pediatric cataract cases. He also stressed ND has never been reported in a sulcus-placed lens or with an anterior chamber lens. "The only thing I've proven clinically is if you take the lens out of the bag, the problem goes away," Dr. Masket said.

Solutions

Luckily, most cases of ND fade with time and rarely need surgical intervention. If ND is going to dissipate on its own, it will be in the first 6 months. But it doesn't always. A handful of patients will remain symptomatic a full year later. Why ND diminishes in some patients and continues to plague others is a mystery. Likewise, no one knows for sure why ND clears up in the first place. Some surgeons believe the patient adapts to the phenomenon over time and stops noticing it as much. Dr. Miller, however, disagrees with that theory. "They don't just get used to it," he said. "It would be like trying to get used to having a ball and chain attached to your foot. You might learn to live with it, but you wouldn't ever get used to it or act like it's not there. I don't think there are patients getting used to it or neuroadapting to it. I think it actually goes away." Dr. Miller believes ND disappears because lens epithelial cells begin to pack into the space between the front and back capsule at the edge of the lens, reducing the difference in refractive index between the inside lens and just outside the lens. "They make the edge of the lens leaky to light," he said. "The light that leaks out illuminates the nasal retina and the shadow goes away." Because ND could simply go away, all surgeons interviewed recommended waiting at minimum of 3 months, but ideally 6 months to a year, before trying anything surgically. During that time period, having the patient wear thick-framed glasses might alleviate the symptoms. "We always try to get patients out of glasses, but this is one case where glasses do help," said Dr. Davison. "Glasses can obscure the image so it makes it less distracting. It puts the shadow in the same category as a frame, and [the patient] doesn't notice it anymore."

"Anything that will block a source of light on the temporal side, like a pair of spectacles, will reduce the symptoms," said Dr. Masket. "Unfortunately, that's not a satisfactory answer for many patients. If you can get thick-framed glasses, it's a good suggestion. It's worthy of a try."

If a patient bucks at wearing glasses, it's time to consider surgery. Dr. Miller's preference is to do a full lens swap, taking out the offending IOL and replacing it with a rounded-edge or plate haptic lens in either the bag or the sulcus.

"I'll put in a plate haptic lens like a STAAR Surgical collamer lens (Monrovia, Calif.) and will orientate the plate haptic in the 3 to 9 o'clock orientation," Dr. Miller said. "The optic is continuous with the haptic, so there's no lens edge to cause that problem anymore." Inserting a "piggyback" IOL, which was first reported by Paul H. Ernest, M.D., associate clinical professor, Kresge Eye Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, is another surgical technique that's proven successful. Dr. Masket explained this technique in detail in the September 2011 issue of EyeWorld (page 16). A video of Dr. Masket's technique is available at www.eyeworld.org/replay.php.

"It's a simple surgery that brings with it a high degree of both technical success and the alleviation of symptoms," said Dr. Masket. "I have heard reports where it hasn't helped 100% or even at all. Nothing is 100%, although in our research, we had either complete or significant reversal of symptoms.

"The problem is you have a condition on which people don't have good facts, and they have a lot of emotions so you get a lot of opinions," Dr. Masket said. With so little clinical understanding of ND, it's easy to see why the phenomenon both frustrates and captivates physicians. Even with a physical intervention, there will be the occasional patient who surgery won't help. In those cases, said Dr. Davison, it's up to the doctor to be a physician instead of a surgeon. "A surgeon repairs things, but a physician sits and listens to the patient and councils him through problems," said Dr. Davison. "You can explain all the wonderful advances we have, and there are miraculous techniques and materials that we work with, but they are not like the good Lord's original equipment. There are limits to what we can do."

Editors' note: The doctors interviewed have no financial interests related to this article.

Contact information

Davison: jdavison@wolfeclinic.com; via RN Carol Loney, cloney@wolfeclinic.com

Masket: sammasket@aol.com; via assistant Ann McLean, avcweb@aol.com

Miller: kmiller@ucla.edu

留言

張貼留言